While readers of Roberts’ novels over the decades have appreciated his work for its vivid imagery and historical thoroughness, scholars have been somewhat uncertain how to classify Roberts’ status among American authors.

Janet Harris (A Century of American History in Fiction: Kenneth Roberts’ Novels, 1976) eludes to this uncertainty among scholars. Harris defines the qualities of the ideal historical novel as embodying “both historical accuracy and literary excellence” (5).

John Farrar (as discussed in Harris, 5)1 identifies three categories of historical fiction:

- Historical Novel: “character motivation and reactions take precedence over the historical setting” (Harris, 5).

- Period Novel: a novel that “reflects an interest in detailed sociological background of certain time and place in history” (Harris, 5).

- Romance Novel: a novel that “subordinates setting and character to plot; adventure and suspense become the chief elements” (Harris, 5).

Harris notes that scholars have typically categorized Roberts a a writer of historical romance novels (5). This make sense if one were to limit the focus of Roberts’ novels on the adventures of Steven Nason on the high seas (Captain Caution; Lively Lady), of Peter Merrill with the Benedict Arnold’s army (Arundel; Rabble in Arms), or of Langdon Towne with Major Robert Rogers (Northwest Passage). However, to merely identify Roberts as a romance novelists downplays the necessary role his historical research and details play in his novels.

For some, apparently, Roberts’ novels were too historical. In his autobiography I Wanted to Write, Roberts recounts the time when Oliver Wiswell was being considered for the Pulitzer Prize (IWW, 356-57). However, no novel was chosen for the Pulitzer that year (1940) to Roberts’ relief. He eventually found out in a roundabout way the reason why Oliver Wiswell was not chosen: according to someone on the committee, it was “history disguised as fiction.”

And so we see – to some degree – why scholars have been somewhat ambivalent about Roberts’ novels. As such, we often don’t see Roberts included among America’s most noted novelists and authors. For instance, in Adventures in American Literature: Laureate Edition (1963), Roberts is not included among the authors highlighted, though he “deserve[s] attention” (128). Other such works fail to mention Roberts at all. Which leads me to the point of this post…

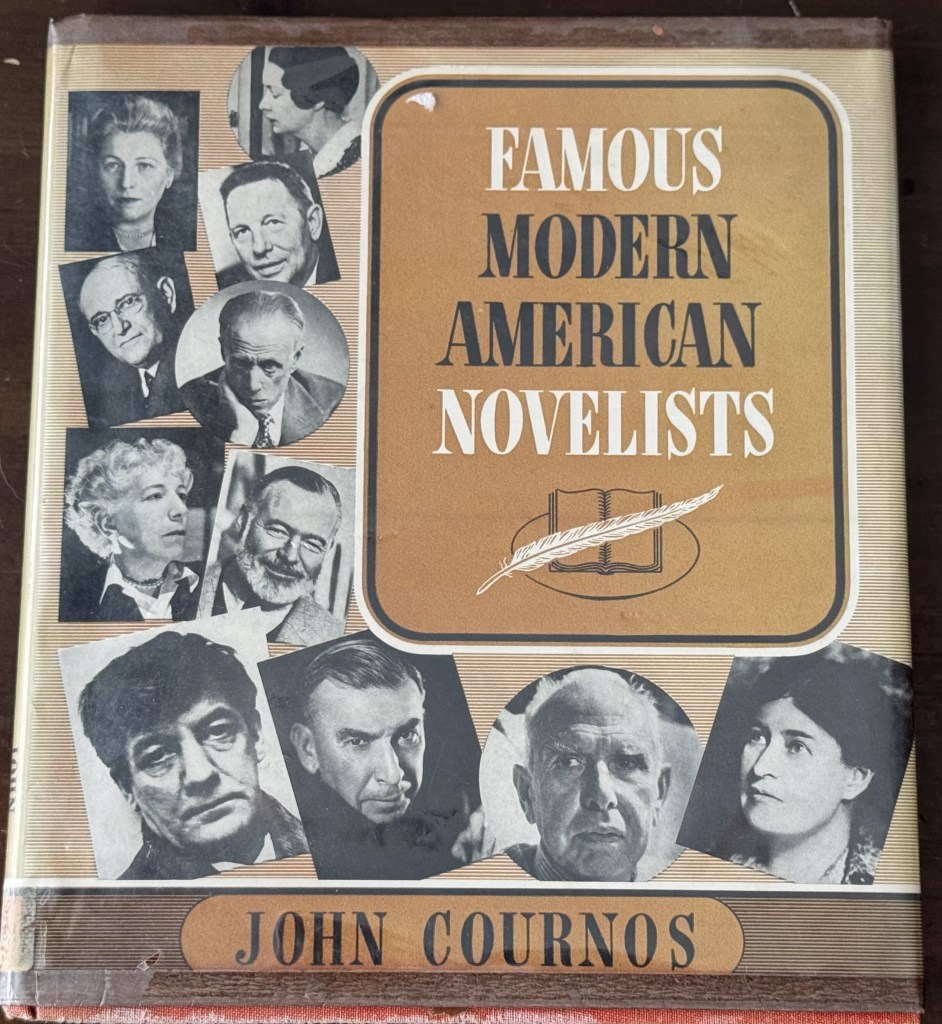

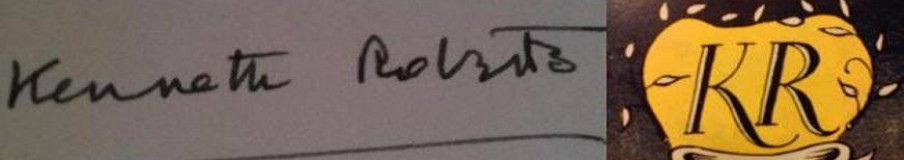

Recently I stumbled upon the above pictured book, Famous Modern American Novelists (1952) by John Cournos and Sybil Norton, which is a part of the Famous Biographies for Young People series. By 1952, Roberts had moved into writing about Henry Gross and water dowsing (though he had begun writing Battle of Cowpens toward the end of his life, which was published posthumously). Yet, his reputation as a chronicler of early American history was well-established – so much so that his Chronicles of Arundel “and those [novels] which have followed can be used for the study of history in schools” (Cournos & Norton, 43).2

At least in Cournos and Norton’s opinion, Roberts was both a novelist and a historian – it was not an either-or situation:

No one has proved more certainly than Kenneth Roberts has that historical facts need not be dry. He is a factual and lively reporter of history (44).

With the publication of Northwest Passage, it (and Roberts’ other novels)

had actually aroused a new and growing interest in the history of our country; in its romance, glories and tragedies, its stupidities and ignominies, which is a splendid thing for the youth of a democracy (45).

In reference to Oliver Wiswell, Cournos and Norton says of Roberts’:

he tries to tell the truth as exactly as he possibly can, allowing some flexibility, of course, for dramatic incident and exciting adventure, while avoiding extremes and trying to see the opposing points of view (46).3

In closing out his brief biography of Roberts, Cournos and Norton provide an assessment of Roberts’ ability as novelist and historian:

He is surely one of the most readable historical novelists writing in our day. Already, in his lifetime, he is regarded as something of a classic. No doubt this is due not alone to his great skill in story-telling but also because what he writes has the effect of being founded on truth (47).

So, while scholars have been somewhat ambivalent about Roberts as a novelist, Cournos and Norton emphatically laud Roberts has both historian and novelist (albeit in a book for youth).

Postscript: Unfortunately, we see interest in Roberts fall sharply not long after his passing in 1957. Granted, he was the focus of several dissertations and articles within two decades of his passing; however, after Jack Bales’ two significant scholarly works on Roberts, there’s been rather little written of Roberts and his novels.

- John Farrar, “Novelists and/or Historians,” Saturday Review of Literature, 28 (February 17, 1945). ↩︎

- See also page 44, where Cournos claims that “many schools use his books regularly in their English and History courses.” Regarding the use of Roberts’ novels in the classroom, see: William J. Graham, “English ‘Revolutionized’”, and Alfred T. Hill, “The Class Finds a Northwest Passage,” in Kenneth Roberts: An American Novelist (New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1938). ↩︎

- Here I anticipate the objections of some who note Roberts’ tendency to allow his biases to color his view of historical fact. I address this tendency elsewhere. My point here is not to agree or disagree with Cournos; rather I seek to merely portray his assessment of Roberts. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.