[Contrary to my revised purpose for this site, this post will be more of a fan post. Looks like I can’t avoid it!]

With the 2023-2024 academic year come to an end and grading is a distant memory, I’ve taken it upon myself to read books I want to read. After completing Scott’s Antiquary, I started two separate novels only to find they failed to interest me (I’m sure I’ll get to them soon).

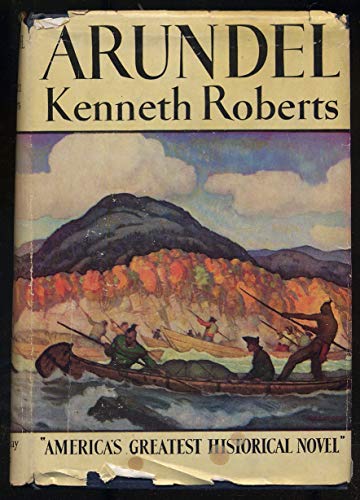

I have been reading Roberts’ I Wanted to Write – sort of a second book on my nightstand to pick up when I was weary of my other reading. However, my mind has been craving a good novel as opposed to non-fiction, so I decided to pick up his novels and read them in the order in which they were written. As such, I have been reading through Arundel. I must confess, I’ve only read Arundel once, and that was a rather long time ago. It’s been so long that I feel as though I’m reading the novel for the very first time. I’m not complaining, though; I’ve been reading Roberts for a while, so it’s nice to read from a different perspective.

I am approximately 1/4 of the way through the novel, but already I have a number of thoughts that have come to mind.

Character Introductions

Usually, when I want to read a Roberts’ novel, my go-to is Rabble in Arms. My entry point to Roberts’ works was Rabble in Arms. As a junior in high school, I had to pick a book for a book report; I recall walking around in my high school’s library, unsure of what book to read. I saw the school’s copy of Rabble in Arms, and the title caught my eye, so I decided to check it out, and the rest is history.

Though Arundel is his first novel, for some reason I view Rabble in Arms as the first in a long line of novels. So…when it’s been a while between readings, I instinctively go for Rabble in Arms. I also view the character trajectories through the lens of Rabble, as well as the time line of Roberts’ Chronicles of Arundel (incorrect though it is).

But, since I’ve begun reading Arundel, it’s like I’m reading Roberts from a new perspective, particularly in regard to character introductions.

Marie de Sabrevois

For instance, Marie de Sabrevois is a key protagonist in Rabble in Arms. Nathaniel Merrill – the narrator’s brother – is infatuated with Marie de Sabrevois, and she attempts to use this to her advantage.

In Arundel, we meet Marie as young Mary, a native of Arundel and a neighbor of sorts with young Steven Nason. We also learn how she becomes associated with the Frenchman Henri Guerlac – both of whom seek to undermine the American colonies during the American Revolution.

Cap Huff

We also learn in Arundel Cap Huff’s backstory. Cap Huff is Roberts’ comedic relief in several novels, most notably Arundel and Rabble in Arms. (He’s one of my favorite characters, especially in Rabble). Perhaps the most interesting aspect of his backstory is the origin of his name “Cap.” Nason notes that people mistakenly assume Cap’s name is short for “Captain” (understandably so), and Cap does little to nothing by way of preventing this assumption. His name, however, is actually Saved From Captivity.

As Nason narrates in Arundel, Cap’s parents and two older parents were brought to Kittery after Lovewell’s Fight. Shortly thereafter, Cap was born. Having just been saved from captivity, his parents fittingly named him Saved From Captivity (see p. 24 in Arundel for the brief backstory).

Phoebe (Marvin) Nason

In Rabble in Arms, Steven Nason (the narrator of Arundel) plays a significant, but background, role in the novel. We always see Nason with his wife, Phoebe, who is an excellent shipwright, sailor, trader, etc. Nason and Phoebe are inseparable and make a fantastic team. If you only read Rabble, you would think Nason and Phoebe were childhood sweethearts.

We learn in Arundel that they did indeed know each other as children. However, they were anything but sweethearts. Nason fell in love with Mary (later Marie) at an early age and remain devoted to her even after her kidnapping. Though Phoebe was a prominent part of Nason’s life (she eventually worked in the in he ran), she was more like a sort of gadfly – a persistent thorn in Nason’s side. Granted, I say this from Nason’s perspective – I believe Phoebe knew from the start she loved Nason and that they were mean for each other. She was rather patient and persistent with Nason, and she was not afraid to speak her mind to him. The blinders eventually fall off Nason’s eyes – no longer blinded by the allure of Mary – and sees Phoebe for who she truly is.

Phoebe is another one of my favorite characters. It’s well-known that Roberts’ female characters are rather under-developed as individuals – undynamic, lacking depth and personality, and predictable. Phoebe, on the other hand, seems to defy Roberts’ typical portrayal of important female characters.

K.R.’s View on Religion

If you have read just a small number of Roberts’ novels, or essays, or some combination of both – his silence on religion is rather deafening. Granted, he’s not completely silent on religion; but, by and large, the religious lives of his characters play a negligible role in the story. Given my background in theology and philosophy, I find Roberts’ silence on religion rather curious when you consider how much religion factored into the Revolution. For example, the First Great Awakening was still present in the memories of colonists when agitation toward the Crown took hold and spread among the Colonies. Yet, Roberts does not address the religious context that surrounded and infused the Revolutionary War.

However, Roberts is not completely silent in regard to religion. For instance, in Book I of Arundel, young Steven Nason and his father (also Steven) encounter an “exhorter” (p. 102) from Boston, Rev. Ezekiel Hook. Rev. Hook had arrived at Swan Island as part of his mission to “talk to settlers who had no meeting houses, and to lead the Abenakis to follow the white man’s Great Spirit, if they did not already do so” (102). The elder Nason was none too happy to see Hook, and from pages 103 – 106, Nason lays into Hook, railing Puritan Christianity for its treatment of Native Americans, its greed for power and money through unfair land speculation, and for their insistence on being in the right regarding worship and God.

The elder Nason’s view of Puritan Christianity – adopted by the younger Nason – is rather telling of Roberts’ own views of Puritanism, and likely of organized religion in general as well (see to Jack Bales in his biography on Kenneth Roberts, p. 42-43). Though Lukásc suggests that the author of the ideal historical novel remains silent (that is, their personal opinions and biases do not shine through), Roberts has the tendency of allowing his narrators to reflect to a large degree his own views and opinions (Lukásc, The Historical Novel).

It should be noted that Roberts does not dismiss religion outright. Further, based on everything I’ve read of his works up to this point (and there are some works I’ve yet to read), he does not appear to me to be an atheist nor an agnostic. Rather, he is rather critical of organized religion and those who seek to use religion for their own selfish ends. This is not unlike Roberts’ criticism of government and government officials – the paragon of inefficiency and wastefulness.

In closing, it seems there’s always something to learn when reading Roberts’ novels and non-fiction, regardless how many times you’ve read it. There’s much more I could write about, but I must save it for another post.

You must be logged in to post a comment.